Like many architects who are interested in building performance, I’m interested in the concept of Passivhaus, Like many architects, I’m also interested in ideas. Most of our buildings have aimed for the particular, and have aimed to more than just have low energy bills and use resources wisely. I mentioned to Olly Wainwright that my worry about Passivhaus was that it was a one size fits all approach, and was jumped on by a few zealots who have signed up to the cause because, well, if you’re a true believer, and this how you make your living, there’s no room for doubt is there? Passivhaus Zealots, I’m not attacking you – just wondering whether in your beliefs, there’s room for a conversation? We want the same thing, ultimately, don’t we?

What I meant is this. Architecture – the design of a building for a given brief, a given context and given client is a very particular thing, and we’ve always used each building as a mini manifesto with which to explore a particular issue and a particular way of being in one place, for one particular group of people. Glenn Murcutt used to say that a building needs to do more than just perform well, and I’m with him. My nervousness about Passivhaus is the potential distraction that the performance is the end game.

I’ll explain what I mean with three of our houses, each which has a very different design approach, and each which explores a different idea about building envelope and performance.

First up, Moonshine. In many ways it’s a very naïve building, but the big idea, the big guiding concept, works. We wanted absolute transparency in the living spaces on the ground floor, partly to let the idea of landscape run through the building, and partly to let the building have a flexible skin, which we could adjust depending on the weather, light and wind pattern, and spill outside accordingly. Upstairs, we wanted to feel like we were camping in the treetops – to be able to slide back big boors in our bedroom at night and hear the forest noises, and see the canopy from the big ash tree almost as if it was in the room.

First up, Moonshine. In many ways it’s a very naïve building, but the big idea, the big guiding concept, works. We wanted absolute transparency in the living spaces on the ground floor, partly to let the idea of landscape run through the building, and partly to let the building have a flexible skin, which we could adjust depending on the weather, light and wind pattern, and spill outside accordingly. Upstairs, we wanted to feel like we were camping in the treetops – to be able to slide back big boors in our bedroom at night and hear the forest noises, and see the canopy from the big ash tree almost as if it was in the room.

It’s an uber lightweight building (everything had to be carried down a track in order to construct it), and the solid bits are super insulated, but it’s a very leaky building. I was over influenced by those great antipodean shacks where everything opens up and shuts down, and where the concept of a building is a finely tuned yacht that you constantly adjust in response to weather. The best thing about is the solar gain on bright winter days that mean that we don’t need any heating until after dark. The fuel for heating is all from the woodland around the house, that we cut, stack and dry the previous year.

It’s an uber lightweight building (everything had to be carried down a track in order to construct it), and the solid bits are super insulated, but it’s a very leaky building. I was over influenced by those great antipodean shacks where everything opens up and shuts down, and where the concept of a building is a finely tuned yacht that you constantly adjust in response to weather. The best thing about is the solar gain on bright winter days that mean that we don’t need any heating until after dark. The fuel for heating is all from the woodland around the house, that we cut, stack and dry the previous year.

Could this have been a Passivhaus? No way – we enjoy opening windows too much, and we like the house being able to physically respond to the adjacent mircroclimate. Moonshine isn’t a particularly good building, but it does do some things well.

Moonshine is deficient because there’s far too much glass, and it’s far too lightweight. We tried to remedy this in Starfall – the next building we did in the same valley, for a family much like our own with a bunch of rumbustious growing children who would leave the doors and windows open. The big idea in terms of building envelope is thermal mass. I wanted – to the point of obsession – a super-insulated thermal envelope with as much exposed thermal mass as possible, and far less glass. So, we focused on placing windows were necessary to gain views or the first chinks of morning light, and, importantly (a repeated mantra of ours) to allow the landscape to run through the building and cooking area to be right between two large sliding screens that could disappear into the walls.

Moonshine is deficient because there’s far too much glass, and it’s far too lightweight. We tried to remedy this in Starfall – the next building we did in the same valley, for a family much like our own with a bunch of rumbustious growing children who would leave the doors and windows open. The big idea in terms of building envelope is thermal mass. I wanted – to the point of obsession – a super-insulated thermal envelope with as much exposed thermal mass as possible, and far less glass. So, we focused on placing windows were necessary to gain views or the first chinks of morning light, and, importantly (a repeated mantra of ours) to allow the landscape to run through the building and cooking area to be right between two large sliding screens that could disappear into the walls.

This family wanted, like ours, an ambiguous relationship with the outside, one where the surroundings felt like part of the house and an extension too it. And what’s great is that they can do this – they can leave the doors and screens open in chilly spring or autumn weather, and because of all the heat retained in the thermal mass, the temperature hardly drops. Of course it isn’t as efficient as a Passivhaus, but it is still uber efficient, and, critically, it reinforces the notion that a house isn’t a sealed little box that you go into or out of, but instead an intelligent envelope that allows occupants to dwell in a responsive way to one particular place.

This family wanted, like ours, an ambiguous relationship with the outside, one where the surroundings felt like part of the house and an extension too it. And what’s great is that they can do this – they can leave the doors and screens open in chilly spring or autumn weather, and because of all the heat retained in the thermal mass, the temperature hardly drops. Of course it isn’t as efficient as a Passivhaus, but it is still uber efficient, and, critically, it reinforces the notion that a house isn’t a sealed little box that you go into or out of, but instead an intelligent envelope that allows occupants to dwell in a responsive way to one particular place.

Nowhere more true is that than the Caretaker’s House. This time, we wanted a super-insulated ultra lightweight responsive well-sealed envelope, and we wanted to make it from wood from the forest in which it sat. Pretty much every significant part of it is. We used 5 different species of timber for the house – for the frame, the cladding, the floors, the worktops etc. There’s no wet trades in the building, which sits on tiny mini steel piles.

Nowhere more true is that than the Caretaker’s House. This time, we wanted a super-insulated ultra lightweight responsive well-sealed envelope, and we wanted to make it from wood from the forest in which it sat. Pretty much every significant part of it is. We used 5 different species of timber for the house – for the frame, the cladding, the floors, the worktops etc. There’s no wet trades in the building, which sits on tiny mini steel piles.

But, in terms of Passivhaus principles, that’s as far as it goes. It’s heated entirely with waste wood from other manufacturing processes that exist on site, and, like the other houses, the occupants wanted the house to have a symbiotic connection with the surrounding woodand – one where it could extend or retreat into the surrounding landscape, depending on weather, mood or occasion.

Maybe I’m just instinctively prejudiced against regulations and legislation. Maybe I’m an over enthusiastic hopeless romantic, but as far as I can tell, this symbiosis with context, this delight in the particular, this desire to have a flexible responsive skin that is operated intelligently by the occupants would be banished if we’d tried to go for Passivhaus conformity – and yet all of these houses have tiny running costs and very low emissions.

Maybe I’m just instinctively prejudiced against regulations and legislation. Maybe I’m an over enthusiastic hopeless romantic, but as far as I can tell, this symbiosis with context, this delight in the particular, this desire to have a flexible responsive skin that is operated intelligently by the occupants would be banished if we’d tried to go for Passivhaus conformity – and yet all of these houses have tiny running costs and very low emissions.

I may be wrong, but that’s great, tell me I’m wrong, and let’s work together to find a way that environmentally responsible buildings that perform well can also do the other stuff – in embracing the particular and the delightful, and respond directly to site, context and use.

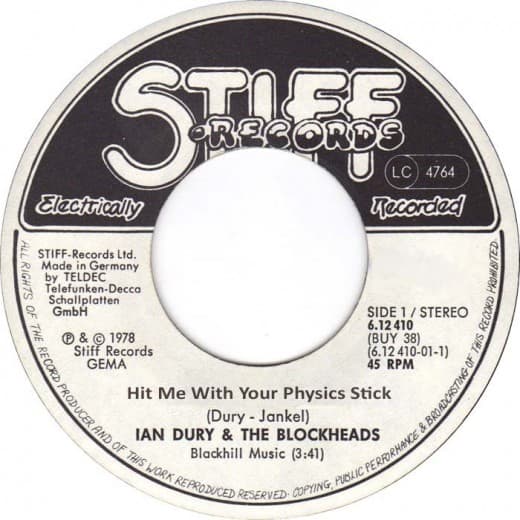

Don’t hit me with your physics stick, because I get the Physics of Passivhaus! I suspect my resistance to embracing Passivhaus wholeheartedly – or rather, my nagging unease somewhere around Passivhaus is also that I’m not convinced that reduced energy costs automatically leads to good architecture. I know most of you don’t either, but I’ve been sent many examples recently of fully certified Passivhaus buildings, and predominately, the key issue I’m told about is reduced running costs (generally at the expense of greater construction costs). Of course we aspire to reduced energy use and the resultant running costs, but much of the time it feels that for many Passivhaus builders, this is the overriding ambition for the building and of course, a building has greater responsibilities that this. Similarly, a symbiotic connection with context means more than being able to open the windows.

Don’t hit me with your physics stick, because I get the Physics of Passivhaus! I suspect my resistance to embracing Passivhaus wholeheartedly – or rather, my nagging unease somewhere around Passivhaus is also that I’m not convinced that reduced energy costs automatically leads to good architecture. I know most of you don’t either, but I’ve been sent many examples recently of fully certified Passivhaus buildings, and predominately, the key issue I’m told about is reduced running costs (generally at the expense of greater construction costs). Of course we aspire to reduced energy use and the resultant running costs, but much of the time it feels that for many Passivhaus builders, this is the overriding ambition for the building and of course, a building has greater responsibilities that this. Similarly, a symbiotic connection with context means more than being able to open the windows.