Piers Taylor is speaking with Andrew Grant at the Bath Literature Festival on Saturday 5th March at 2.45pm, where they will explore the significance of future urban landscapes. If you’d like to come booking is HERE

Moonshine. 10 Years On.

Ten years this year since we moved into Moonshine.

Ten years this year since we moved into Moonshine.

Studio. One Year On.

Pretty much a year to the day since we moved in to the Visible Studio.

Pretty much a year to the day since we moved in to the Visible Studio.

On Making

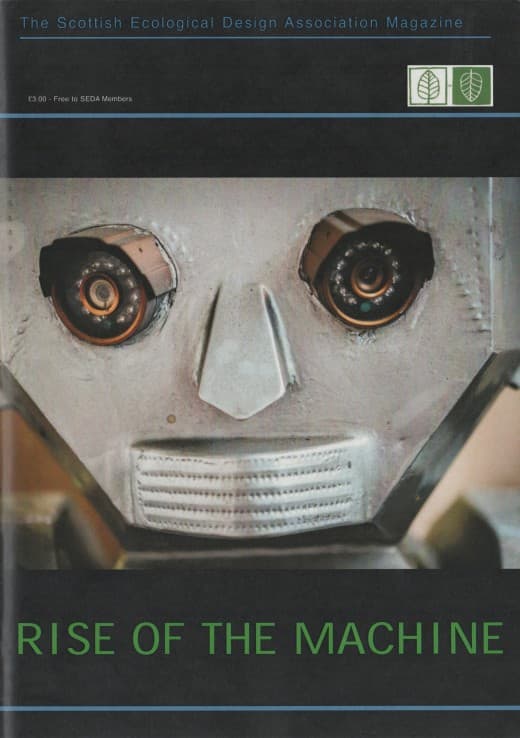

(Piers Taylor was asked to write an extended piece on his interest in ‘making’ for the Scottish Ecological Design Association magazine, how this interest developed through Studio in the Woods, and how this informed Invisible Studio. This is the full, unedited text.)

Over the last decade or so of practice, research and teaching, I have become increasingly interested in how the process of design can be re-imagined to benefit from the discoveries that emerge from the process of construction. Clearly, there has been a resurgence of interest in ‘making’ over the last few years and while I have little doubt that making for its own sake is rewarding, for the large part my interest in making is not just as an end in itself, but instead as a process of investigation that leads to new insights.

There has been a boom in design/build workshops and courses recently, and most are still structured in such a way that the ‘design’ stage is a precursor to the ‘build’ stage, rather than weaving together designing and making in reciprocal fashion to allow the discoveries that arise during the build process to be incorporated into the ‘design’ – or rather, BE design. But, what if the process of design was turned around, and instead of using the control mechanism of an empirical set of fabrication documents to banish variables, contingencies, chance encounters, or, God forbid, mistakes, and instead, allow the real time choreography of a process where drawings and construction evolved in parallel?

This is a way of working that I’ve been moving towards. Underpinning this move towards a different way of working is a fascination in using full scale making as a method of testing ideas, and using the process of consolidation or accumulation as a design tool. Rather than refining a prototype and then unveiling something perfectly formed and defect free, I am interested allowing a prototype to be continuously modified and adapted so that it is allowed to become the ‘final’ piece, with modifications and mistakes made manifest.

Note the use of ‘final’ in inverted commas here. A combination of architects’ fear, innate control-freakery and the legacy of the modern movement has meant much contemporary architecture has an obsession with the perfect, flaw free and sanitized jewel, frozen in time. There is an enduring idea in architecture of the photograph of the just completed building, free from the process of construction, the potential chaos of people and furniture, and certainly free of the patina of occupation, weather or aging that builds up. In my work, I’m not terribly interested in the ‘final’ – I’m more interested in the ‘ongoing’.

For me, the evolution of this thinking stemmed from building my own house, over ten years ago. It opened my eyes to a sense of what the process of construction and material exploration could offer. What followed was an about turn in my method of teaching, and the same year that I built the house a group of us started to do something we called ‘Studio in the Woods’. We didn’t ‘set it up’ – I’m suspicious of things that are ‘set up’ or premeditating too much – Studio in the Woods just evolved out of friendships with other architects, and casual conversations about how it may be fun to do a workshop with some students in the woods around my house. Taking a cue from Dylan, we just threw the cards up in the air to see where they landed, and trusted we’d be agile enough to catch things as they happened.

Where they landed – or what came out of the first weekend of Studio in the Woods 10 years ago – set the pattern for subsequent years. We’d test ambitious ideas quickly, at 1:1, using timber felled and milled on site. For me, the giddy and heady freedom that came with being able to work directly, with materials to hand and with the chaos and surprise of inventing on the hoof was amazing. Critically, it provided me a new model of working – one where new architectural forms and relationships could be discovered, rather than merely willed. One of the big questions many architects have is – if we don’t merely want to use precedent or deterministic processes, how do we discover architectural form? For me, allowing construction, material exploration and full scale making in real time went some way to answering this. In addition, it provided a freedom from a world where only ‘skilled’ people could make things. The material relationships that are formed by alternatively skilled (conventionally unskilled) people are often more interesting to me than those that are perfectly, and blindly, crafted. I’m a big fan of the ‘bodged joint’ where evidenced in it is the maker’s journey of discovery.

I also, through Studio in the Woods, discovered a world that conventional modernism had banished – a world of material sensibility where judgment was more important than design rhetoric or received notions of material relationships. This journey away from a place where making is over controlled has been fascinating. I grew up listening to music by people that were told they couldn’t play or sing. For me, this made their music better, particularly as it depended on delivery, and this delivery was freed from the tyranny of technique. Architecture is, or was, full of concern with ‘correct’ detail and material expression. Mark E Smith called Rock n Roll the ‘mistreating of instruments to explore feelings’, but in architecture, even at its most loose and improvised, there has conventionally been little room for badly made buildings – or buildings made without due regard for technique. My buildings are often badly made in the received sense and often have little regard for technique. This doesn’t mean I don’t care about how they are made – On the contrary, I care enormously about how my buildings are made, and the elemental relationships between components.

Partly through taking part in Studio in the Woods, but also through delivering the Big Shed at Hooke Park for the Architectural Association, I realized that there was no room in conventional practice for me. About three years ago, I resigned from the practice that I’d co-founded (Mitchell Taylor Workshop), and, inspired by an impromptu and adhoc coming together of interesting people at Hooke Park and Studio in the Woods, formed Invisible Studio – to allow me to practice in a way that makes sense to me.

Studio in the Woods doesn’t really exist – it was the original invisible studio. There’s no institution, no one owns it, no organisation funds it, no one audits it, and it is beholden to no one. Invisible Studio is similar. I have no fixed work force, no formal company – just a loose, unstructured collection of people that work together when the conditions are right, and not when they aren’t.

The simple motivation is the creative work. With Studio in the Woods there was never any commitment to ever work together again. There is no hierarchy, no presumptions and certainly no succession planning. Studio in the Woods isn’t a charity, a company or a co-op – and nor is Invisible Studio. Like Studio in the woods, Invisible Studio isn’t a practice – it’s a kind of anti-practice. It is just people, who work together with no labels, titles or expectation.

Alongside this, the world of timber has become more and more fascinating to me over the years since the first Studio in the Woods, and I’ve recently bought a woodland with my partner, which we manage alongside practice and family life. We’ve recently built our studio in it with timber from the woodland using friends and neighbours in the construction, and almost no drawings. We’re busy now delivering 2 buildings for the National Arboretum using a similar method. What’s curious is that it is technology that allows me to work in this way – to run an office from a laptop with cloud computing and a smart phone. I’m never sure what is next, or what is around the corner, but my modus operandi is to ensure Invisible Studio makes no commitment to anyone’s future or anyone’s ongoing livelihood, especially my own. It exists merely to carry out interesting work. If the work is good enough, we find a way to make money and thrive creatively. Nothing else matters.

© Piers Taylor 2015

Learning From

Piers Taylor was asked by Chris Foges, editor of Architecture Today to write a piece for the ‘Learning From’ column in AT.

His brief was: ‘The idea of the piece is that the writer reflects on someone – or something – that has had a formative influence on their own thinking or practice as an architect. That could be a tutor, a former employer, a book or exhibition, or even a particular experience – architectural or otherwise.’

Learning From

Like many architects I’ve had plenty of inspiring ‘teachers’ who’ve provided guidance at various stages of my life. Certainly, too, there have been many formative texts for me. But it was the summer workshop Studio in the Woods that provided so much in terms of clarifying a vision for a method of practice. There were three key things that Studio in the Woods helped clarify and establish for me – practice (lack of) structure, an attitude to making, and an approach to timber.

No one started Studio in the Woods and in many ways it doesn’t exist. It evolved from a few friends getting together in the summer time to test ideas at 1:1 while working alongside architecture students. The vision for an invisible studio – or, rather Invisible Studio came from this – a loose, unstructured collection of people that worked together when the conditions were right and not when they weren’t.

With Studio in the Woods there was never any commitment to ever work together again. There was no hierarchy, no presumptions and certainly no succession planning. Studio in the Woods isn’t a charity, it’s not a company or a co-op – and nor is Invisible Studio. Like Studio in the woods, Invisible Studio isn’t a practice – it’s a kind of anti-practice. It is just people, who work together with no labels or titles, with no commitment or expectation.

Studio in the Woods helped me understand that there could be a vehicle for practice the outside the super-conventional model adopted by almost every architect. Like Studio in the Woods, Invisible Studio makes no commitment to anyone’s future or anyone’s ongoing livelihood – it exists merely to carry out interesting work. If the work is good enough, we find a way to make money and thrive creatively. Nothing else matters.

Also, before Studio in the Woods, I was suspicious of the moralising around ‘making’ which came with all the baggage inherited from the arts and crafts movement with its notions of truth around material and structural expression. Studio in the Woods showed me how making could be used as a design tool to underpin practice, and be used in an exploratory way as a mechanism for discovery, rather than the pious making where something is made well for its own sake. I came to enjoy the ‘bodged joint’ – knowing that making wasn’t an end, but instead the beginning of a process of design. At Studio in the Woods, we made quickly and greedily, with improvised structures built in an adhoc way, free from the tyranny of an office.

Through Studio in the Woods I discovered a world that conventional modernism had banished – a world of material sensibility where judgment was more important than design rhetoric. The world of timber has become more and more fascinating to me over the years since the first Studio in the Woods, and I’ve recently bought a woodland with my partner, which we manage alongside practice and family life, and we’ve recently built our studio in it with timber from the woodland using a design method that has evolved through a decade or so of using full scale making as the essential component of design. This, and the way of life that is Invisible Studio ultimately feels as if it would have been impossible without the lessons from Studio in the Woods, which will be back next year, 10 years after we ran the first one.

Categories

- 100k house

- Articles

- brexit

- Caretaker's House

- Christchurch

- current

- East Quay Watchet

- film

- ghost barn

- Glenn Murcutt

- Heroes

- Hooke Park

- House in an Olive Grove

- Invisible Studio

- longdrop

- Mess Building

- Moonshine

- On the Road Again

- passihvaus

- piers taylor

- piers,taylor

- press

- Projects

- Riverpoint

- Self Build

- Stillpoint

- Studio Build

- Studio in the Woods

- talks

- Trailer

- truss barn

- Uncategorized

- Vernacular Buildings

- watchet

- Westonbirt

Tags

- caretaker's house

- design and make

- Design Build Workshop

- Design Make

- east quay

- east quay watchet

- Glenn Murcutt

- green timber architecture

- Hooke Park

- Hooke Park Big Shed

- Invisible Studio

- Low Impact House

- moonshine

- Onion Collective

- piers taylor

- Piers Taylor Architect

- piers taylor invisible studio

- self build

- self build architect

- Starfall Farm

- Stillpoint Bath

- studio in the woods

- Sustainable Architecture

- The house that £100k built

- timber architecture

- Timber House

- timber workshop

- visible studio

- westonbirt architecture

- westonbirt tree management centre