More details and tickets HERE

More details and tickets HERE

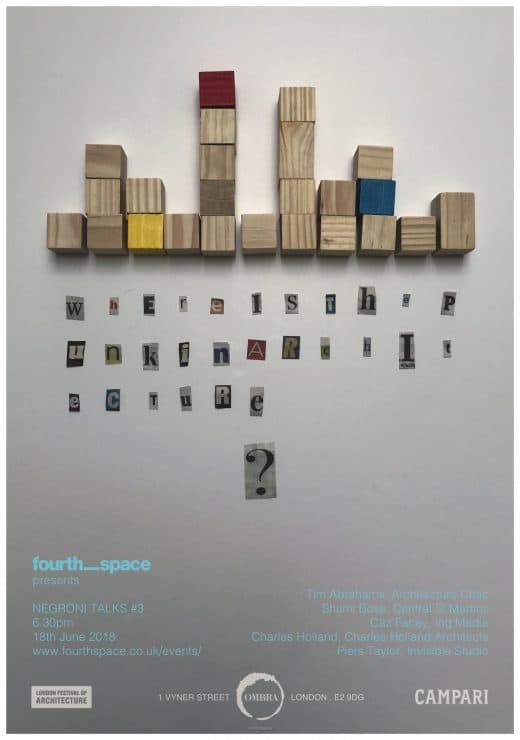

Where is the Punk in Architecture?

Craft Connecting Architecture

Oliver Lowenstein’s freewheeling review of a series of talks at the Craft Connecting Architecture conference from Fourth Door. Piers Taylor was one of the keynote speakers.

Last November’s Craft Connecting Architecture Architecture Connecting Craft conference at London’s Building Centre sought to explore craft and architecture’s meeting spaces. Bringing together designers, architects, crafts-people and the maker world, the day focused on crafts people working on architectural and landscape related projects, and architects engaging with craft practice. Radical in how the conference drew the different disciplines together, we look at how effective it was, and what worked and what didn’t. So how effective was it?

It was only some way into the day’s last presentation that the word ‘materiality’ turned up, the speaker drawing on one of those tried and trusted workhorse terms – nomenclature – that professions use. Lights light up and alarm bells ring, it’s an architect talking. And indeed it was.

The one-day conference, Craft Connecting Architecture – Architecture Connecting Craftheld in London’s Building Centre at the end of November, had, up to that point steered circuitously clear of such archi-speak orthodoxy. Co-organised by the two University of the Creative Arts Farnham campus centre’s, the Crafts Study Centre and the International Textiles Research Centre, the eight speakers were a decidedly idiosyncratic mix. Designer makers who didn’t make, crafts-people who did, and two keynote speakers, both of whose off-centre work contribute to the redefinition of what ‘architectural’ can mean and encompass.

Those two speakers, the Dutch textile and landscape garden designer Petra Blaisse, and the one-time semi-mainstream and gadfly to the profession currently, Piers Taylor, gave what were easily the most inspiring and thought provoking talks of the day. Blaisse, whose Amsterdam based Inside Out design studio has built a formidable reputation since working with Dutch architecture’s erstwhile enfant terrible Rem Koolhaas and his OMA outfit, showed two OMA co-projects: Casa Da Musica Concert Hallin Porto, Portugal and the Doha Water Recipe Garden. Inside Out designed and made the curtains for the concert hall – one of which drops a full 22 metre’s – a vivid example of how curtains are a signature speciality of Blaisse’s. As she talked the small, eighty-person audience through the fishnet knotted weave of the white and black curtain, Blaisse demonstrated the singular way in which textile crafts, as much as textile design, and its lightness, can interplay with the heavy solidity of a concrete auditorium.

It was not exactly a complete surprise that the head of UCA’S International Textile’s Centre, professor Lesley Millar, had invited Blaisse to the conference. Millar has long been an energetic supporter of Japanese textile and fabric art – which occupies a similar in-between space between formal artistic practice, and ambient interior architecture. This in-between quality is also underlined by Blaisse’s other main love, gardening, fusing design elements with landscape. The collaborations with OMA have again been particularly fruitful here, for instance the 2016 Water Recipe Garden sitting in the parched Doha cityscape. She also showed a number of smaller, appealingly light hearted and playful pieces: an umbrella-like installation piece – described as a personal mobile garment made of a translucent silver material, and the technologically clever sliding curtains that surreally slid around the Dutch Pavilion at the 2012 Venice Biennale. Blaisse emphasised the technical dimension of these projects; curtains and other façade’s used to filter light or buffer sound, or their climate and circulatory design functions, as much as their jaw dropping decorative appeal. Seeing architectural related work from a non-architectural perspective was particularly refreshing. And all through, the language that Blaisse uses to describe her work seemed alien and distant from the ways architecture is usually articulated; curtains ‘emancipated’ from building, confusing interior spaces merging with the external world outside of buildings, or creating, shown in another example, a landscape with a meandering, rather than straight, path, form hardly following function. Or, as Blaisse described it, a ‘lyrical’ path. Had I ever, I began to wonder, heard an architect talking about a building as being lyrical?

The two crafts-people who followed, suffered from having to present their ideas in the afterglow of Blaisse’s opening blast. Christopher Tipping and Richard Kindersley, each operating in contrasting craft contexts, explored their work interestingly if undynamically. Tipping moved from an early craft background – ceramics, into a career as a designer maker; working principally in public, generally, urban contexts, mainly on regeneration and civic projects. The care and concern evident in street furniture and signage for a series of initiatives in Southampton, spoke to the craftsperson in Tipping, even as he acknowledged that ideally, what he wished for and what craft depends on, is time: something not usually available when working on public and municipality commissions. Kindersley, a letter, type and font engraver, came closest to the traditional image of the twentieth century craftsman. He showed a number of works where lettering and other forms of engraving were part of larger architectural, or building works. Threaded through his talk, was an ongoing plea regarding the disappearance of the quiet timeless qualities associated with the hand made, compared to the world of the fast moving 21st century social media universe. The sincerity, and genuine heartfelt conviction that Kindersley was voicing was clear, and I felt for Kindersley, watching his life work, vocation and craft at the cusp of disappearing, must be difficult. But his lament is familiar, and has been around a long time, stretching right back to the Arts & Crafts era. As he sketched the situation it also became apparent that he didn’t, beyond an emotional appeal to what loss means – with so many heritage crafts being on the edge of extinction – have answers regarding their survival, revival and resurgence. One thought, too late now, but possible for future consideration, is that the organisers might have found a fresh-faced craft-person, part of the current maker generation who have embraced various at risk crafts; an exchange between youth and age could have been thought provoking.

The story was similar in the afternoon, when Philip Koomen, the furniture designer, and Linda Brassington, standing in for Jo Macullum who was ill, gave considered, if emotionally flat, talks.

Koomen discussed a series of furniture commissions for particular buildings, most recently the Herzog DeMeuron University of Oxford Blatnavik School of Government, along with less recent private commissions. The furniture was beautifully turned out, but the sense that Koomen had much to say about the work was missing, other than that he’d designed it, and his small team had then faithfully made the designs. Any sense that these were the outcome of some kind of search for answers to larger questions – of meaning, of context, of the future of craft – that had spurred him on through the years, was absent. That crafts can demonstrate technical skills can feel not enough at times. That it shies away from critical reflexivity hinders its sense of vitality and intensity; that – as has been observed in another context, jazz – craft could be more important than your life.

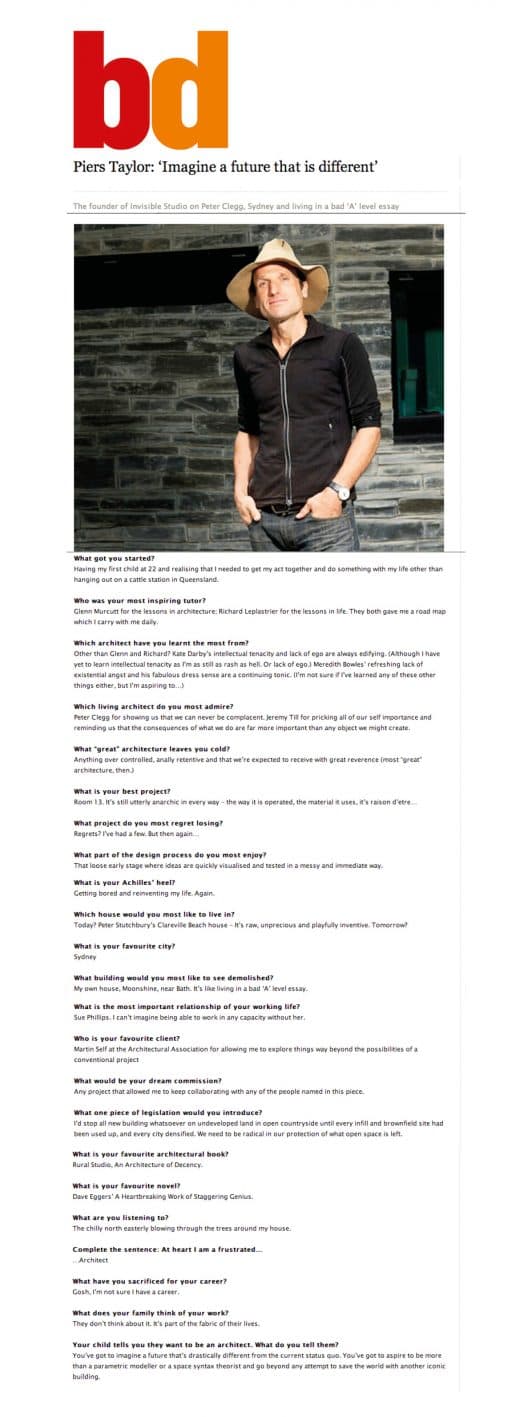

As in the morning sessions, Both Koomen and Brassington spoke in the slipstream of that afternoon’s keynote – given by the one-time mainstream architect, Piers Taylor. Taylor, who had arrived during lunch and speaking a mile a minute spent much of his talk pacing the floor like a man consumed; trying to uncover the place where a certain hidden secret he was intent on unravelling, was leading him. The questions he asked – essentially of himself – though bringing the audience along for the ride, did this time come across as potentially almost life and death. Or, at least, when there were answers to the questions, it almost sounded like they’d maintain his sense of mental health. Taylor’s reputation precedes him. Having walked away from a partnership in a small but successful commercial practice, Mitchell Taylor Workshop, after a life changing visit in 2013 to his architectural mentor, the Australian cult figure, Glenn Murcutt, when given a chance, Taylor has denigrated the mainstream ever since. This talk was no exception. His antipathy and alienation from his one time architectural world couldn’t be clearer as he attacked a meaty sampling of the professions shibboleths. Yet, his obsession suggests a man who, despite an exotic architectural afterlife and re-invention as the one man Invisible Studio, hasn’t completely reconciled himself to his past. Taylor’s recent adventures in embodied experiential making – at the AA’s Hooke Park, at his self built home in some deep forest wilds some place out in Bath’s back country, and with the ongoing Studio in the Woodsdesign & make workshops – do look as if, spiritually, they have nurtured him, and kept him going over the last few years. Various points, the issue of control – pervasive in architecture – and its disconnect from the conditions of making, from the everyday in landscape, and from the vast majority of everyday people, was passionately made, if never really escaping the irritating trope that architects have of putting themselves at the centre of the story. From a social and developmental psychological and broader science perspective, an obvious next step is to ask why so many architects seem habitually to do it?

Whether the majority of Craft Connecting Architecture’saudience took on these aspects of Taylor’s talk wasn’t clear. To the irritation of some of the organisers, Taylor disappeared immediately after his talk was over, with the result that there was no follow up. Something, actually, quite characteristic of the architectural profession, and suggesting Taylor’s limited interest in engaging with this primarily non-architectural audience. Would the craft people present, both speakers and audience members, have connected with Taylor’s craft inflected architectural related issues, or were they too far removed from its concerns? While Tipping praised artisans, and Koomen the team who translate his designs into realised furniture, neither they, nor the other crafts speakers broached the wider community and its connection or otherwise with their work; beyond some amused words on the great general public’s assertions about the waste of tax payer’s money such civic projects entail. As with so many of these types of events, the potential for more informal exploration within a discussion, loses out to keeping to the days schedule, and readying the next speaker to step up to the lectern.

All this led me to wonder how curious these crafts-people were about the labyrinth of ‘meaning’ questions, which Taylor had strode into. Was it Taylor and Blaisse’s intensity of interest which drove them, emotionally as much as intellectually, and which distinguished each from the other speakers? Did it have something to do with the difference in disciplines; these were both architect related practitioners after all? Or was it something to do with a relation to risk and keeping to the safe territory of technical skill and competence?

If the last speaker, architect Roz Barr, might have cast light on these points, it didn’t happen. Instead Barr gave an orthodox architectural talk about a series of her projects, completed either while working at the respected Eric Parry Architects, or with her own studio, illustrating the overlap with craftsmanship at various turns. It was in this context that the significance of materials surfaced, and the moment the current ubiquitous architectural term, ‘materiality’ was deployed. Portland stone, cast iron, cross-laminated timber, and copper facades were all referenced. And while there was much to admire, this was again a conventional talk, neither following Taylor into the thicket of issues where his singular path has led him, nor the individuality ‘in between spaces’ out of which Blaisse has created such an idiosyncratic career. The path was straight, with neither meander, nor flow, or so it seemed. Once again there was the sense of an invisible boundary in the presentation, to do with risk and exposure, that wasn’t to be crossed; the emotionally cool word ‘materiality’ the appropriate descriptive to be reached for, rather than the poetic ardour and presence uncovered in the single word, ‘lyrical.’

Oliver Lowenstein

Craft Connecting Architecture

Categories

- 100k house

- Articles

- brexit

- Caretaker's House

- Christchurch

- current

- East Quay Watchet

- film

- ghost barn

- Glenn Murcutt

- Heroes

- Hooke Park

- House in an Olive Grove

- Invisible Studio

- longdrop

- Mess Building

- Moonshine

- On the Road Again

- passihvaus

- piers taylor

- piers,taylor

- press

- Projects

- Riverpoint

- Self Build

- Stillpoint

- Studio Build

- Studio in the Woods

- talks

- Trailer

- truss barn

- Uncategorized

- Vernacular Buildings

- watchet

- Westonbirt

Tags

- caretaker's house

- design and make

- Design Build Workshop

- Design Make

- east quay

- east quay watchet

- Glenn Murcutt

- green timber architecture

- Hooke Park

- Hooke Park Big Shed

- Invisible Studio

- Low Impact House

- moonshine

- Onion Collective

- piers taylor

- Piers Taylor Architect

- piers taylor invisible studio

- self build

- self build architect

- Starfall Farm

- Stillpoint Bath

- studio in the woods

- Sustainable Architecture

- The house that £100k built

- timber architecture

- Timber House

- timber workshop

- visible studio

- westonbirt architecture

- westonbirt tree management centre