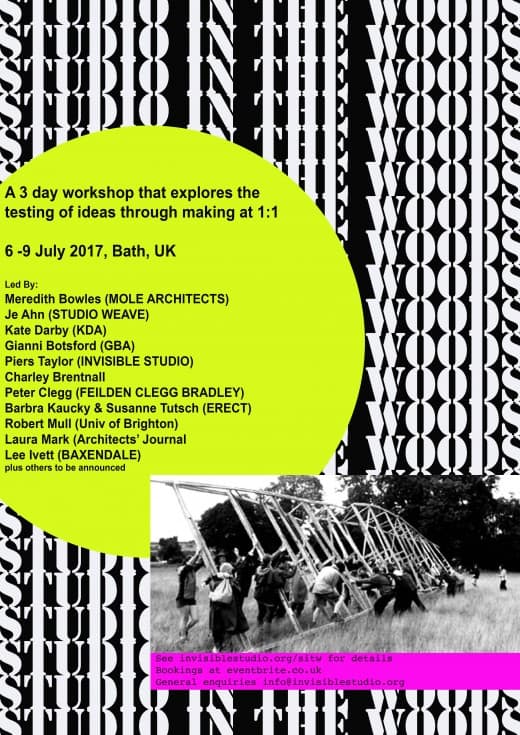

Studio in the Woods was back this year – bigger and better than ever. 70 Students of architecture and makers along with 15 architects as group leaders and critics descended on Invisible Studio for a extraordinary long weekend of making. 5 groups led by Gianni Botsford, Kate Darby, Piers Taylor, Meredith Bowles, Charley Brentnall, Je Ahn, Le Ivett, Lynton Pepper, Barbara Kaucky, Susanne Tutsch, Fergus Feilden and Akos Juhasz with support from Laura Mark, Zoe Berman and Jack Hawker constructed a range of structures that explored an idea relating to the woodland in which they were located. Evening lectures were given by Niall McLaughlin, Martin Self and Robert Mull, who were then joined by Peter Clegg and Ted Cullinan for the final review. Alan Matthews, Bernard Twist, Martin Osbourne and Simon Schofield also provided much needed technical support. See HERE for more details.

Studio in the Woods was back this year – bigger and better than ever. 70 Students of architecture and makers along with 15 architects as group leaders and critics descended on Invisible Studio for a extraordinary long weekend of making. 5 groups led by Gianni Botsford, Kate Darby, Piers Taylor, Meredith Bowles, Charley Brentnall, Je Ahn, Le Ivett, Lynton Pepper, Barbara Kaucky, Susanne Tutsch, Fergus Feilden and Akos Juhasz with support from Laura Mark, Zoe Berman and Jack Hawker constructed a range of structures that explored an idea relating to the woodland in which they were located. Evening lectures were given by Niall McLaughlin, Martin Self and Robert Mull, who were then joined by Peter Clegg and Ted Cullinan for the final review. Alan Matthews, Bernard Twist, Martin Osbourne and Simon Schofield also provided much needed technical support. See HERE for more details.

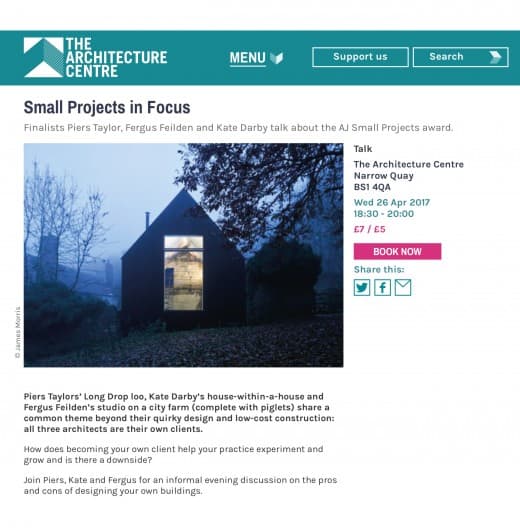

AJ Small Projects Talk

Piers Taylor will be talking at the Architecture Centre in Bristol about the research value of self initiated projects. Book HERE

Piers Taylor will be talking at the Architecture Centre in Bristol about the research value of self initiated projects. Book HERE

Rook Lane Chapel Talk

Book tickets HERE

Book tickets HERE

Studio in the Woods

More information HERE

More information HERE

How British Housing Can Rediscover its Soul

Clare Nash has recently published a new book, for which Piers Taylor wrote the foreword, below. The book is available to buy HERE.

Clare Nash has recently published a new book, for which Piers Taylor wrote the foreword, below. The book is available to buy HERE.

Great Britain has some of the most beautiful, appropriate and resilient housing in the world. The majority of this housing was built before 1940, was not designed by architects, and forms the backbone of our towns, villages and cities. In many ways, it used to be so easy: we built unselfconsciously, using local materials, customs and techniques – effortlessly forming our own vernacular.

Since the war however, almost all of the housing stock that we have produced has been substandard to the point that it has wrecked many of the towns and villages that had survived unscathed for generations. This was caused by poor planning policy and urban design, ideologically misguided architects and perhaps most importantly, the shortsighted selfishness of volume house builders who refuse to put good design before quick profit.

Most volume housing has not been designed by architects – but to a certain extent, our vernacular housing showed that it didn’t necessarily need to be. If we followed certain fundamental rules of thumb we could create decent, ordinary resilient houses that together formed a cohesive beauty greater than an a collection of individual buildings.

The housing that was designed (often over designed) by architects in the post war period didn’t fare much better – communities were uprooted and re-housed in buildings lacking the fundamental ingredients that allowed these communities to reform and thrive in the way that they had previously.

The ability for housing to become ‘place making’ has, by and large, become lost from our nation’s psyche. The tyranny of the ‘dream home’ perpetuated by populist TV programmes means that many people aspire to a ‘statement’ detached dwelling with a double garage and a sea of tarmac, rather than the simple dignity of a house, in a street, that purposely subjugates its own individuality for the greater good of place. This latter type of housing – the house that becomes the street, that becomes the neighbourhood, that becomes the town – is effortlessly democratic.

This does not mean that we need to hark back to a mythical golden age of pre war housing: on the contrary, as Clare Nash has painstakingly researched, there is much contemporary housing that is exceptional, and shows what is possible in any context in the UK.

Much of the housing that Clare writes about in this book is affordable, alluring, durable and democratic, and shows that there is another way other than that provided by the volume house builders. Clare’s study shows how well we can do it when we want. She restates the importance and significance of the ordinary, the everyday, and the vernacular. In the face of the impending ransacking of the landscape by new and inappropriate housing, Clare’s exemplars show the potential for a beautiful built future to house successive generations effectively.

A manifesto for change, this book needs to be thrust into the hands of all developers and house builders. It also needs to be read by everybody else – to wean us off our addiction to the false promise of the ‘exclusive, individual luxury home’. Let us hope we can look forward to a new era of effortless vernacular place making, using the building blocks of the versatile and appropriate housing shown here.

© Piers Taylor

Categories

- 100k house

- Articles

- brexit

- Caretaker's House

- Christchurch

- current

- East Quay Watchet

- film

- ghost barn

- Glenn Murcutt

- Heroes

- Hooke Park

- House in an Olive Grove

- Invisible Studio

- longdrop

- Mess Building

- Moonshine

- On the Road Again

- passihvaus

- piers taylor

- piers,taylor

- press

- Projects

- Riverpoint

- Self Build

- Stillpoint

- Studio Build

- Studio in the Woods

- talks

- Trailer

- truss barn

- Uncategorized

- Vernacular Buildings

- watchet

- Westonbirt

Tags

- caretaker's house

- design and make

- Design Build Workshop

- Design Make

- east quay

- east quay watchet

- Glenn Murcutt

- green timber architecture

- Hooke Park

- Hooke Park Big Shed

- Invisible Studio

- Low Impact House

- moonshine

- Onion Collective

- piers taylor

- Piers Taylor Architect

- piers taylor invisible studio

- self build

- self build architect

- Starfall Farm

- Stillpoint Bath

- studio in the woods

- Sustainable Architecture

- The house that £100k built

- timber architecture

- Timber House

- timber workshop

- visible studio

- westonbirt architecture

- westonbirt tree management centre